Finance Think supports an increase in the minimum wage to preserve the living standard of its recipients.

The key question is not whether the minimum wage should increase, but at what pace and on which economic foundations. An excessive increase in the minimum wage and all other wages in the economy without a parallel increase in newly created value entails several risks.

The first risk is pressure on prices. Inflation in January declined to 3.2% year-on-year, down from 4.1% in December, but it remains above the level considered stable and above the euro area level of 1.7%, which is an important reference given the fixed exchange rate of the denar against the euro.

Persistent inflation in North Macedonia is the result of several factors, ranked by their importance:

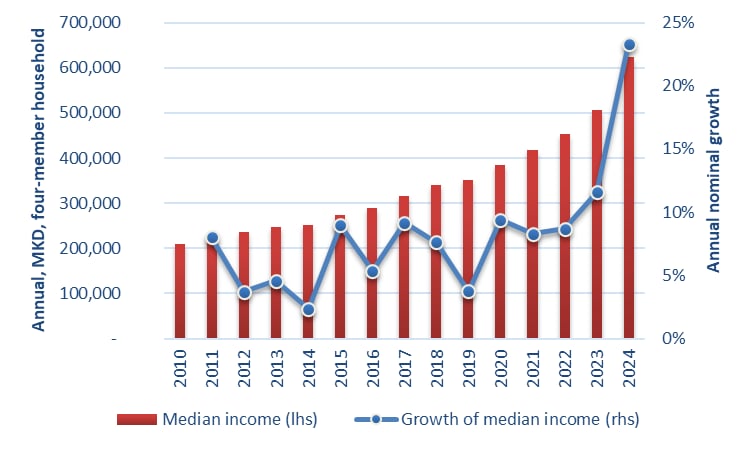

1. Increased income in the economy, resulting from strong real wage growth over the past several years, largely due to chronic labor shortages in the labor market; as well as from the significant increase in pension income, which over a relatively short period exceeded 30% of the average pension (Graph 1).

Graph 1 – Dynamics of Median Income in the Economy

Source: Own calculations based on the Survey on Income and Living Conditions of the State Statistical Office.

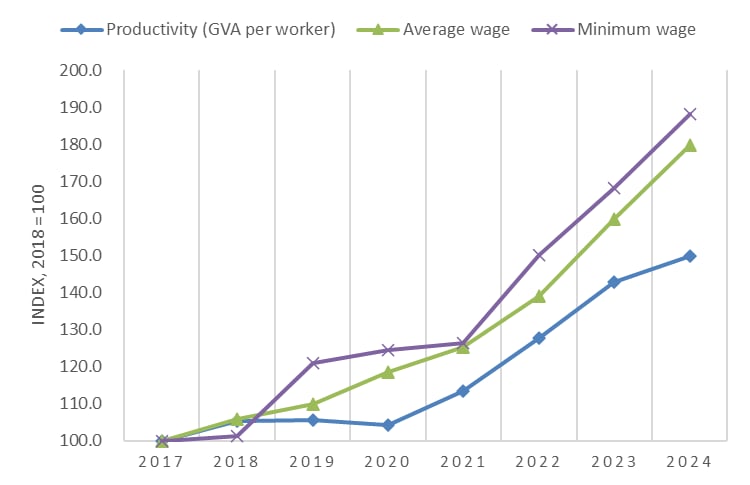

Especially in the second half of 2025 and at present, persistent inflation is largely the result of demand-side pressure. Wages – the main component of income in the economy – grew faster than productivity over almost the entire period, such that in 2024 compared to 2017, the average wage was higher by 79.9%, the minimum wage by as much as 88%, while productivity increased by only 49.8% (all indicators are nominal growth, Graph 2). This divergence between income and productivity is macroeconomically unsustainable and directly translates into price pressure.

Graph 2 – Labor Productivity and Wage Growth, Annual Growth

Source: State Statistical Office.

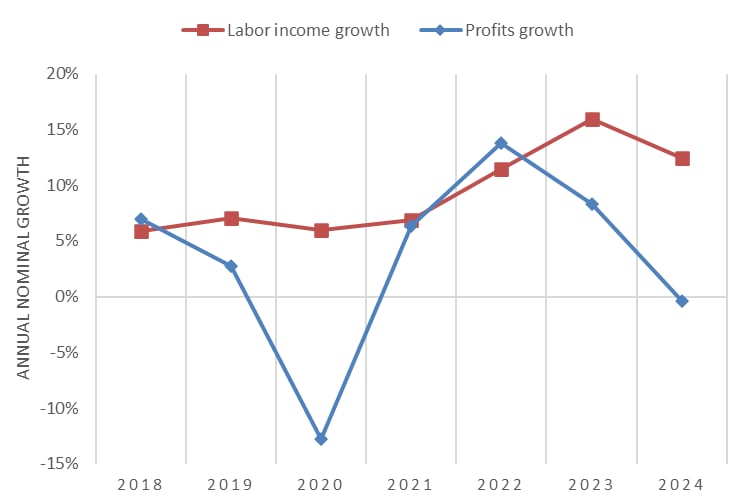

2. The behavior of certain actors along the supply chain, particularly in food sub-markets, prevented the easing of price pressure from global food markets from being transmitted quickly and proportionately to the domestic economy. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that company profits grew more slowly than household incomes, which does not provide strong support for the claim that a shift in income distribution in favor of employers is the source of inflationary pressure (Graph 3). In other words, inflation at present cannot be explained simply and exclusively as “corporate greed,” but rather as a combination of strong demand and structural market constraints.

An exception is the crisis year 2022, when profit growth outpaced household income growth, indicating that firms passed global price pressures onto final consumers – possibly more than proportionately – contributing to profit accumulation. This supports the so-called “solidarity tax,” which was later repealed by the Constitutional Court; as well as full support for the implementation of the Unfair Trading Practices Law and monitoring potential anti-competitive behavior by the Commission for Protection of Competition.

Graph 3 – Corporate Profits and Workers’ Income, Annual Growth

Source: State Statistical Office.

3. Inflation expectations have also been raised, in part, by repeated short-term measures of freezing prices and margins on food products.

Accordingly, a potential excessive increase in the total wage bill in the economy over the short to medium term would result only in persistent prices, i.e., inflationary pressure that would be difficult to contain without particularly restrictive monetary and fiscal measures. For social dialogue, it is especially important that the minimum wage be aligned with the creation of new value added in the economy, that is, with productivity.

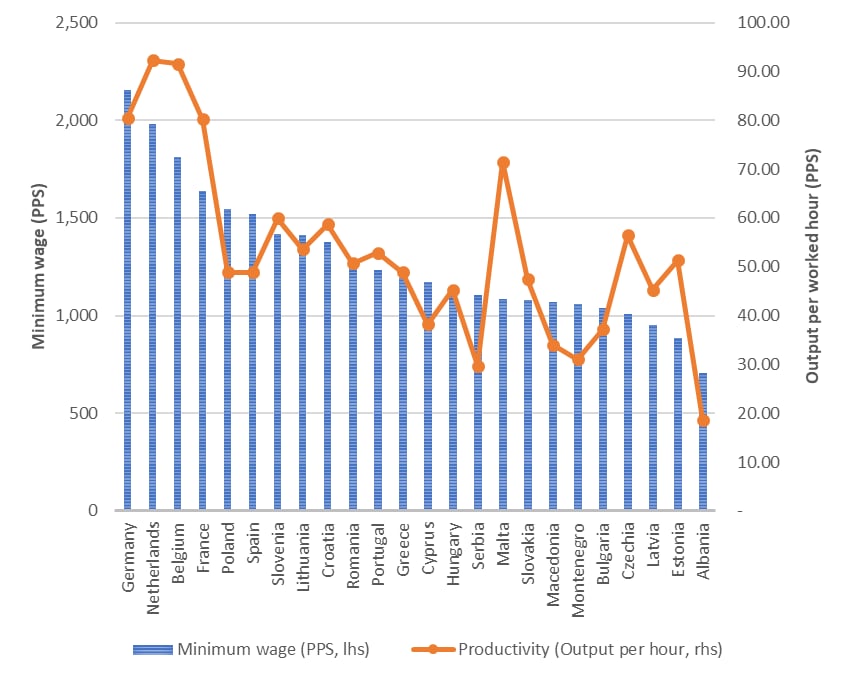

According to currently available data, North Macedonia has a minimum wage (measured by purchasing power standard) similar to or the same as Malta, Slovakia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria, while having higher productivity (again measured by purchasing power standard) only than Montenegro among these countries. By contrast, Czechia, Latvia, and Estonia have lower minimum wages but higher productivity (Graph 4).

Graph 4 – Minimum Wage and Productivity in Europe, by Purchasing Power Parity (2025)

Source: ILOSTAT and Eurostat. Luxembourg and Ireland are not shown due to very high productivity. Countries not shown are those without a statutory minimum wage.

The second risk is disruption of fiscal consolidation. After the pandemic, North Macedonia has pursued a limited pace of fiscal consolidation, implying a gradual reduction of the budget deficit and public debt. However, the budget deficit is still projected above 3% of GDP, and total public debt is approaching and during 2026 will exceed the psychological threshold and fiscal rule of 60% of GDP. In this context, the expert community calls for fiscal consolidation to be viewed not only through the prism of the budget deficit, but also through the need to significantly eliminate unproductive expenditures on the spending side of the budget.

A major expenditure item is state aid, i.e., subsidies. In the period 2019–2022, North Macedonia introduced subsidized social contributions for wage increases ranging from 600 to 6,000 denars per worker per month. This subsidy was the second-largest form of state aid after agricultural subsidies (or third, if COVID-19 state aid in 2020 is included; see Graph 5). Undertaking obligations for state wage subsidization not only prevents easing inflationary pressure but also represents a direct attack on fiscal consolidation and a transfer of costs from the private sector to all taxpayers, and should therefore be fully excluded as a policy option.

Graph 5 – State Aid by Type in 2020

The third risk is disruption of the labor market. In conditions of a tight but lethargic labor market (with an activity rate that is not increasing), an excessive increase in the minimum wage will not lead to higher unemployment. Such an outcome is unlikely, given labor market dynamics and past empirical evidence confirming that the link between the minimum wage and layoffs in North Macedonia is very weak. However, this is due to the fact that employers may resort to other adjustment mechanisms, primarily de-formalization or semi-formalization of jobs.

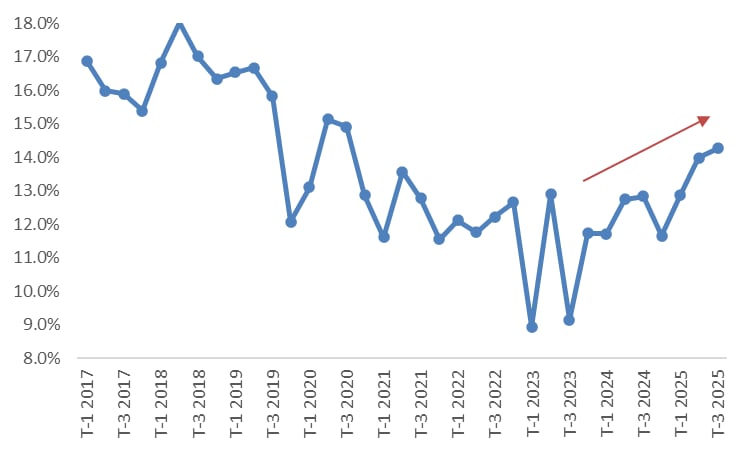

This would imply the absence of a written employment contract (fully informal worker) or insuring a worker for fewer hours than actually worked and paying the remainder through so-called envelope wages (partially informal worker). This adjustment channel under conditions of an excessive minimum wage increase is very likely, given the rising trend in the share of informal workers in recent quarters (Graph 6). This type of adjustment is particularly harmful because it undermines both worker protection and the state’s revenue base.

Graph 6 – Share of Informal Workers in Total Employment

Source: State Statistical Office.

In conclusion, the increase in the minimum wage is socially justified, but it must be aligned with productivity growth and the real capacity of the economy. Otherwise, excessive wage increases generate persistent inflationary pressure, constrain the space for fiscal consolidation, and increase the risk of de-formalization of labor relations. Therefore, the key challenge is not whether the minimum wage should increase, but at what pace and on which economic foundations, in order to preserve both workers’ purchasing power and macroeconomic stability.

Finance Think recommends that the Government actively engages in social dialogue as a third key party and mediator between workers and employers, providing reasoned, evidence-based support. Recognition of the factual situation by all participants in social dialogue is a fundamental prerequisite for preserving both workers’ living standards and macroeconomic stability.